AN 8-YEAR-OLD LAW, A REGULATOR'S FURY: 5 SHOCKING TWISTS IN THE JINDAL POLY FILMS SAGA

December 4, 2025

BMP & Co.

BMP & Co LLP

1.0 Introduction: The David vs. Goliath Battle That Could Rewrite the Rules

In the world of corporate finance, minority shareholders are often seen as passengers on a ship steered by powerful promoters and management. Their ability to challenge the course of the company is perceived as limited, if not entirely symbolic. However, a landmark case currently unfolding before India’s National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) is poised to challenge this long-held narrative in a dramatic fashion.

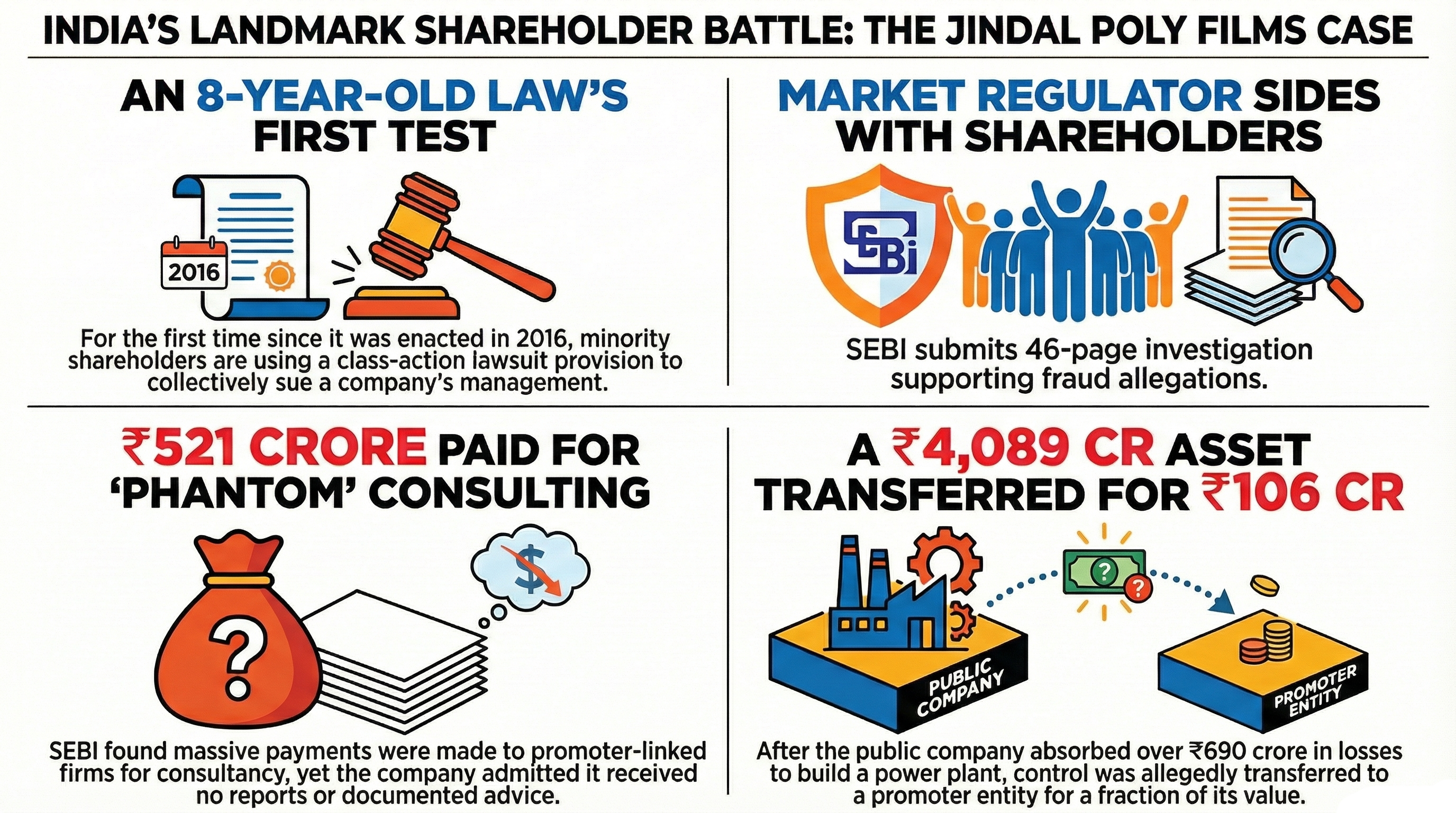

The case, Ankit Jain v. Jindal Poly Films Limited, is not just another corporate dispute. It began with an explosive allegation from minority shareholders that the company’s promoters had caused a financial loss of approximately ₹2,268 crore by transferring valuable shares to a promoter-controlled trust at a fraction of their fair market value. This action ignited a firestorm, leading to the very first use of a powerful but long-dormant legal tool: a class action suit under Section 245 of the Companies Act, a provision that has been on the books since 2016 but never used—until now.

This case is more than a legal novelty. It involves staggering financial allegations, a rare and forceful intervention by India's market regulator, and a complex web of transactions that, according to investigators, were designed to systematically drain value from a publicly listed company. Here are five critical takeaways from the saga that could reshape the balance of power between investors and management in India.

2.0 Takeaway 1: An 8-Year-Old Corporate Law Finally Got Its Day in Court

An 8-Year-Old Law Finally Wakes Up

Section 245 of the Companies Act, which allows a group of minority shareholders or depositors to file a collective "class action" lawsuit against a company for prejudicial conduct, came into effect on June 1, 2016. It was designed to empower small investors, giving them a collective voice to challenge corporate wrongdoing. Yet, for nearly eight years, this provision remained dormant on the statute books, an unused weapon in the shareholder arsenal.

The Jindal Poly Films case, initiated in 2024 by minority shareholder Ankit Jain and others, is the first time this provision has ever been invoked. This marks a potential turning point for corporate governance in India, transforming a theoretical right into a practical remedy. For the first time, minority shareholders have a legal mechanism to band together and hold a company’s management accountable for alleged mismanagement on a collective basis.

The case also brings a critical legal question to the forefront. The language of Section 245 states that it applies when a company's affairs "are being conducted" in a prejudicial manner, implying it is for ongoing misconduct. Jindal Poly Films has argued that the law cannot be applied to past actions. However, shareholders argue that in promoter-led firms, information asymmetry often means misconduct is discovered long after the fact, necessitating a broader interpretation. This legal hurdle is significant, as SEBI’s own investigation meticulously details a pattern of alleged misconduct spanning a full decade, from FY 2013-14 to FY 2023-24, bringing the applicability of the law to past actions into sharp focus.

3.0 Takeaway 2: The Market Regulator Stepped In—And Sided with Shareholders

The Regulator Enters the Ring

This is not simply a private legal battle between a company and a group of its shareholders. In a significant development, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the country's market regulator, has actively intervened. Spurred by shareholder complaints and media reports, SEBI launched its own investigation into the affairs of Jindal Poly Films.

After completing a preliminary probe, SEBI took the decisive step of filing an intervention application with the NCLT, submitting its 46-page findings. This specific legal action makes the regulator a party to the proceedings, lending significant weight to the shareholders' claims.

SEBI's findings are damning. The regulator alleges that the promoters of Jindal Poly Films enriched themselves at the expense of minority shareholders through a series of transactions that amounted to financial mismanagement and securities law violations. The significance of this move cannot be overstated. When a powerful regulator like SEBI formally presents evidence of wrongdoing in a private lawsuit, it adds enormous credibility to the petitioners' case and places immense pressure on the company to defend its actions.

4.0 Takeaway 3: The Alleged Fraud Was Masked by a "Slow Bleed"

Hiding a Billion-Dollar Hole with a 'Slow Bleed'

To understand the specific schemes at the heart of this case, one must first appreciate the method allegedly used to execute them without triggering alarm bells. SEBI’s investigation found that the financial damage was not the result of a single, sudden event. Instead, the alleged irregularities were spread out across multiple financial years, from FY 2013-14 to FY 2023-24. This "slow bleed" tactic, as we'll see, allegedly enabled the massive fund diversions detailed below.

SEBI concluded that this "staggered" approach was a deliberate tactic to obscure the true financial impact from investors and the market. In its filing, the regulator noted:

"the adverse financial impact, though significant in aggregate, was dispersed over time and did not manifest as a substantial loss in any single accounting period. Consequently, the share price of Jindal Poly did not reflect the true extent of value erosion".

This is a critical point. By executing write-offs, loan conversions, and asset disposals over several years, the company allegedly prevented investors from connecting the dots and understanding the cumulative loss. This lack of transparency, according to SEBI, effectively masked the erosion of shareholder wealth and impeded informed investment decisions.

5.0 Takeaway 4: Hundreds of Crores Were Paid for "Phantom" Consulting

The Case of the Phantom Consultants

At the heart of SEBI's investigation are massive consultancy payments made by Jindal Poly to two entities linked to the promoters. A sum of ₹366.12 crore was paid to Soyuz Trading Co. Ltd. and another ₹155 crore was paid to Packflex Business Advisory Services LLP.

According to SEBI, these enormous payments lacked any "genuine commercial rationale." The regulator’s most direct and damaging finding came from a simple admission from the company itself.

"Jindal Poly had submitted that it had not received any documentary advisory or consultancy report".

This finding presents a stark example of the alleged fund diversion. Without any reports or documented advice to show for over ₹521 crore in payments, SEBI concluded the transactions were a guise to transfer funds from the public company to its promoters. Such related-party transactions, especially for intangible services like 'consultancy' without clear deliverables, are a classic red flag in corporate governance audits, as they represent a potential pathway for siphoning funds away from public shareholders.

6.0 Takeaway 5: A Power Company Was Allegedly Transferred for Pennies on the Dollar

A Power Plant for Pennies on the Dollar

Perhaps the clearest illustration of the core allegation—that value was systematically moved from the public company to the promoters' private entities—involves a group power company, Jindal India Powertech Ltd.

According to SEBI's findings, Jindal Poly Films funded the power company over the years with loans and preference shares worth ₹690.27 crore, which were later fully written off, causing huge losses to Jindal Poly and its shareholders. Once the public company had absorbed these losses and the power business became valuable, control was allegedly transferred to another promoter entity for a fraction of its worth through a sophisticated maneuver.

Jindal Poly's holding company, Jindal Finance, held a controlling stake of ~51% in the power company. When the power business turned profitable, it issued new shares worth just ₹106 crore to another promoter-controlled entity. Because Jindal Finance did not participate in this new issue, its stake was diluted to ~49%, thereby losing control. In effect, control of a business SEBI valued at approximately ₹4,088.8 crore was transferred for just ₹106 crore, highlighting the central accusation: that Jindal Poly was used to incubate a business, only for that business to be moved to the promoters' private control once it became valuable.

7.0 Conclusion: A New Era for Shareholder Activism in India?

The Jindal Poly Films case is far more than a dispute over corporate transactions; it is a crucial test for India's entire corporate governance framework. It brings together a newly awakened law designed to protect minority interests with a proactive market regulator determined to enforce accountability. This powerful combination could signal a fundamental shift in the balance of power, moving it away from entrenched promoters and toward the small investors who form the backbone of the public market.

The outcome will be watched closely by corporate India. What began with a single minority shareholder, Ankit Jain, has escalated into a full-blown regulatory investigation that puts a major corporate group under the microscope. As the NCLT's decision is awaited, the entire market is left to ponder a critical question: Will this landmark case finally usher in a new era of corporate accountability and empower the small investor to hold even the most powerful companies to account?